The knee joint is the largest joint in the human body, and the joint most commonly affected by arthritis. Knowing about knee anatomy can help people understand how knee arthritis develops and sometimes causes pain.

The knee joint is a hinge joint, meaning it allows the leg to extend and bend back and forth with minimal side-to-side motion. It is comprised of bones, cartilage, ligaments, tendons, and other tissues.

Bones of the Knee

The knee joint acts as a hinge, allowing the leg to extend and bend back and forth.

Three bones meet and move against each other at the knee joint:

- The bottom of the femur (thigh bone) meets with top of the tibia (shin bone)

- The patella (kneecap) glides along a grove located at the bottom and front of the femur

Bones and arthritis: One sign of arthritis is the development of osteophytes, or bone spurs, at the joint. These small growths on bones can create friction and affect a knee’s range of motion.

Articular Cartilage of the Knee

Articular cartilage allows the knee bones to glide over each other and absorbs shock.

Articular cartilage covers the surfaces of the bones where they meet: at the bottom of the femur, the top of the tibia, and the back of the kneecap. Articular cartilage is an extremely slippery, strong, flexible material.

Articular cartilage serves two purposes:

- It allows the bones to glide over each other as the knee bends and straightens

- It acts as a shock absorber, cushioning bones against impacting each other (e.g. during walking)

Cartilage and arthritis: Knee arthritis is defined by the loss of healthy articular cartilage in the knee.

See What Is Knee Osteoarthritis?

Knee Meniscus

Each thick meniscus acts as a shock-absorber, absorbing the energy of impact.

A knee meniscus is a thick pad of cartilage located between the femur and tibia. There are two menisci in each knee:

- The medial meniscus, which is located on the inside of the knee.

- The lateral meniscus, located on the outer side of the knee.

The menisci reduce shock and absorb impact when the knee is moving or bearing weight. They also help stabilize the knee and facilitate smooth motion between the surfaces of the knee.

Knee meniscus and arthritis: A meniscus injury or meniscus degeneration can lead to the wear-and-tear of articular cartilage, and vice versa.

See Understanding Meniscus Tears on Sports-health.com

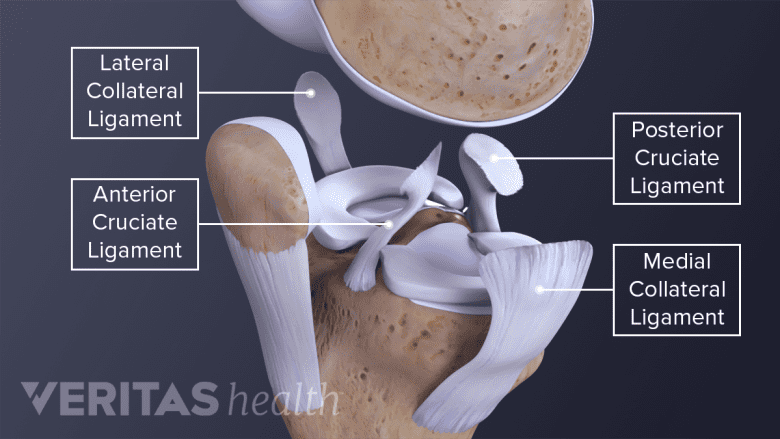

Ligaments of the Knee

Four ligaments protect the knee bones from sliding too far forward or backwards and prevent the knee from moving side to side.

Ligaments are bands of strong tissue that connect bone to bone. The knee has 4 major ligaments that connect the femur to the tibia:

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)

- Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

- Medial collateral ligament (MCL)

- Lateral collateral ligament (LCL)

The ACL and PCL prevent the femur and tibia from sliding too far forward or backward. The MCL and LCL prevent side to side movement.

A relatively new discovery revealed another ligament in the knee that was named antero lateral ligament (ALL), which seems to work in conjunction with ACL.1Farhan PHS, Sudhakaran R, Thilak J. Solving the Mystery of the Antero Lateral Ligament. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(3):AC01-AC04. However, research is still ongoing to clarify its exact job and importance to the function and stability of the knee.

Ligaments and knee arthritis: Knee ligament injuries can lead to joint instability, accelerating the wear-and-tear that leads to knee arthritis. Conversely, knee arthritis can cause joint instability, which puts more strain on ligaments and increases the risk of ligament injuries.

Read more about Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries on Sports-health.com

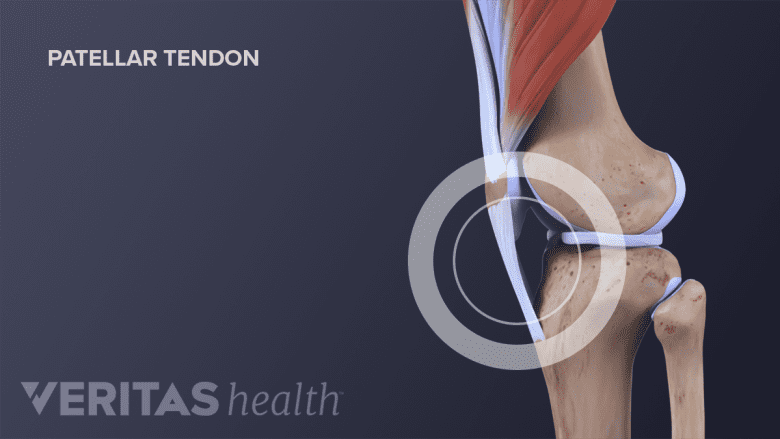

Tendons of the Knee

The patellar tendon connects the kneecap (patella) to the shinbone (tibia), straightens the leg when the quadricep muscles contract.

Tendon tissue connects bone to muscle. The knee’s largest tendon is the patellar tendon.

The patella tendon begins at the thigh’s quadriceps muscles and extends downward, attaching patella to the front of the tibia. When the quadriceps muscles contract the patellar tendon is pulled and the leg straightens.

Tendons and arthritis: Patellar tendon problems can arise from knee arthritis but are more likely to affect athletes who do a lot of running, pivoting, and jumping. If the patellar tendon becomes irritated and inflamed it is called patellar tendinopathy, also known as jumper’s knee.

See Understanding Jumper’s Knee on Sports-health.com

Bursae Surrounding the Knee

Bursae in the knee joint are fluid-filled sacs that reduce friction between the knee bones and soft tissues.

A bursa is a tiny, slippery, fluid-filled sac located between a bone and soft tissue. Like cartilage, bursae reduce friction. But while cartilage reduces friction between bones, bursae reduce friction between bones and soft tissues, such as muscles and tendons—the bursae help muscles and tendons slide freely as the knee joints move. The knee has several bursae.

Bursae and knee arthritis: Arthritis can alter joint biomechanics, leading to irritation of a bursa. When a bursa is irritated and inflamed, it is called bursitis. The most common form of knee bursitis is prepatellar bursitis.

See Knee (Prepatellar) Bursitis

The Knee’s Synovial Membrane and Synovial Fluid

The synovial membrane encapsulates the knee joint and produces synovial fluid that lubricates and nourishes the knee.

A delicate, thin membrane, called the synovial membrane, encapsulates the knee joint. The synovial membrane produces synovial fluid. This viscous fluid lubricates and circulates nutrients to the joint.

- When the knee is at rest, the synovial fluid is contained in the cartilage, much like water in a sponge.

- When the knee bends or bears weight the synovial fluid is squeezed out. Therefore, joint use is necessary to keep joints lubricated and healthy.

The synovial membrane, synovial fluid, and knee arthritis: If the synovial membrane becomes inflamed, it is called synovitis. People who have rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory joint conditions may experience synovitis. In addition, a knee affected by osteoarthritis may have too little synovial fluid, exacerbating joint friction.

Muscles of the Knee

The muscles above and below the knee work together to move the leg: the quadriceps contract as the leg straightens and the hamstrings contract as the leg bends.

For a knee joint to maintain its normal range of motion, the surrounding muscles must be flexible. The muscles must also be strong to provide adequate support to the knee joint.

- Quadriceps muscles at front of the thigh

- Hamstrings at the back of the thigh

- Lower leg muscles, including the gastrocnemius at the back of the calf

Muscles and knee arthritis: Weak muscles will not provide adequate support and stability; therefore, weak muscles can lead to or accelerate knee osteoarthritis.

In addition, recent studies suggest that arthritis may trigger mechanisms that make the surrounding muscles of the knee weaker, creating a cycle where weakness promotes arthritis and arthritis promotes further weakness.2Silva JMS, Alabarse PVG, Teixeira VON, et al. Muscle wasting in osteoarthritis model induced by anterior cruciate ligament transection. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0196682. Published 2018 Apr 30. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.019668,3Silva J, Alabarse P, Teixeira V, et al FRI0768-HPR Muscle wasting in osteoarthritis model induced by anterior cruciate ligament transection Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2017;76:1508.,4Alnahdi AH, Zeni JA, Snyder-Mackler L. Muscle impairments in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Sports Health. 2012;4(4):284-92 This information makes proper knee support exercises in the context of arthritis even more important.

See Knee Exercises for Arthritis

The knee is a large, complex joint with many parts. When one part is injured or degenerates, it can change the knee joint’s biomechanics and have a cascading effect on other parts. The best way to avoid joint degeneration and knee osteoarthritis is to eat a healthy diet, maintain a normal weight, and participate in a routine exercise program.

- 1 Farhan PHS, Sudhakaran R, Thilak J. Solving the Mystery of the Antero Lateral Ligament. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(3):AC01-AC04.

- 2 Silva JMS, Alabarse PVG, Teixeira VON, et al. Muscle wasting in osteoarthritis model induced by anterior cruciate ligament transection. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0196682. Published 2018 Apr 30. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.019668

- 3 Silva J, Alabarse P, Teixeira V, et al FRI0768-HPR Muscle wasting in osteoarthritis model induced by anterior cruciate ligament transection Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2017;76:1508.

- 4 Alnahdi AH, Zeni JA, Snyder-Mackler L. Muscle impairments in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Sports Health. 2012;4(4):284-92